Icelandic isn’t the world’s most common language, but it is beautiful, fascinating, and worth the effort to learn. It will let you travel around one of the most beautiful countries on Earth (no, that’s not just my opinion), read Viking-era sagas and award-winning modern novels, and perhaps most importantly of all, make Icelandic friends.

Yet one of the hardest things about learning Icelandic can be finding the right resources to use. So, read on as we explore the language courses, apps, textbooks, podcasts, YouTube channels, and more that will help you master this beautiful language.

Learn Icelandic with this self-study guide. We’ll break down Icelandic grammar, answer FAQs, and give you some tips for creating your study plan.

- About the Icelandic Language

- How to Learn Icelandic

- What’s the Best Way to Learn Icelandic?

- Is Icelandic Hard to Learn?

- What’s the Easiest Way to Learn Icelandic?

- How Long Does it Take to Learn Icelandic?

- How to Learn Icelandic Fast

- How to Speak Icelandic

- Where to Learn Icelandic: Additional Icelandic Learning Aids

About the Icelandic Language

If you want to understand the Icelandic language, you need to understand the country’s geography. This small, isolated country situated where the North Atlantic and the Arctic Ocean meet was for many years almost inhospitable.

While Icelanders today benefit from an excellent quality of life and a good relationship with nature, earlier inhabitants struggled to eke out a living on a volcanic island with long winter nights and unpredictable weather.

Iceland sits 290 kilometers away from Greenland, 800 kilometers from Scotland, and roughly 1,000 kilometers away from the coast of Norway. The crossing was treacherous, and the prospect of setting sail to a cold, uninhabited island no doubt seemed unappealing.

And so, for thousands of years, Iceland’s only native mammal was the arctic fox – which is believed to have reached the island at the end of the last Ice Age, traveling over the frozen sea. Humans don’t seem to have arrived until the seventh century.

The first people to inhabit Iceland were Gaelic, likely monks from Ireland or Scotland who carved crosses in Icelandic caves in the ninth century. It was the hazardous journey and harsh conditions that attracted them to the island: the voyage was a way to test – and demonstrate – their faith in God.

Their monastic peace was short-lived, however: in 874 CE, Iceland was settled by Ingólfr Arnarson, a Norwegian attracted by the possibilities of tax-free land. Contemporary sources say that the monks left or stopped coming to Iceland, preferring not to share it with “heathens.”

Over the next 54 years, hundreds of Norse people came to Iceland where they claimed land, built farms, and introduced a wider range of animals (including the forefather of the Icelandic pony). DNA evidence shows that there was still Scottish and Irish presence on the island, particularly women, but historians believe it likely that most of the Gaelic inhabitants were slaves captured in Viking attacks on the British Isles.

These settlers were the ancestors of today’s Icelanders. We know this not just because of the DNA testing and the historical and archaeological evidence, but also because of linguistics: modern Icelandic is a direct descendent of Old Norse. In fact, no other modern Scandinavian language is as close to Old Norse as Icelandic is, especially in terms of grammar.

When we look at modern languages, Icelandic has most in common with dialects spoken western Norway. This is despite centuries of Danish rule. In Iceland, this began in the fourteenth century, with the last vestiges of it ending only during World War II.

In fact, Icelandic didn’t become Iceland’s official language until 2011. Yet the language remained in use throughout the centuries of colonization, perhaps due to the almost 2,000 kilometers of distance between Reykjavik and Copenhagen.

Icelandic pronunciation, on the other hand, has changed dramatically. Learning modern Icelandic might enable you to read the sagas written 800 years ago, but don’t expect to sound like Snorri Sturluson, the likely author of Egil’s Saga.

Today, Icelandic is spoken by the roughly 360,000 inhabitants of Iceland – of which around 15% are first- or second-generation immigrants – as well as by Icelandic emigrants around the world. Although all Icelanders learn English and another Scandinavian language in school, they remain proud of their historic and rich language: they celebrate Icelandic Language Day every 16th of November and strive to coin new words rather than accepting loanwords.

How to Learn Icelandic

Every language learner is different, so get ready to take this section with a pinch of Iceland’s famous salt. In fact, you’ll probably want to create a personalized study plan based on four things:

- Your goals

- Your preferred learning style and methods

- How much time you have

- How difficult you find certain aspects of Icelandic

If you’re planning a two-week road trip around this stunning island (lucky you!), you’ll need a different vocabulary from if you were planning to move to Reykjavik for a year. Similarly, if you’re just studying the sagas, whether for your history or literature degree or for pleasure, you probably won’t need to revise Icelandic slang in quite so much detail compared to if you’re planning to chat on Facebook with an Icelandic pen pal.

So, take the time to work out what you want to do in Icelandic and how good you want to become at it. These goals will likely influence both the vocabulary and the skill sets (reading, writing, speaking, listening) you want to hone. While it’s best not to completely neglect any given skill – if for no other reason than that it’s frustrating to discover you can write essays in Icelandic but find it hard to order food in a restaurant – you can then structure your study plan accordingly.

Adjust if you need to. After all, if you find memorizing vocabulary comes naturally to you but you struggle with those Icelandic vowels, it makes sense to reduce your time spent on flashcards and increase your pronunciation exercises and listening tasks.

It’s worth trying a variety of different learning resources until you find the ones that work for you. Someone else’s favorite app or movie might bore you, and there’s no point pushing yourself to use a tool that just isn’t suited to you and how you like to learn.

That’s not to say that you should skip anything you find hard or boring, of course – learning a language will always have its challenging moments. But using the wrong course, textbook, or tutor can make it even more difficult.

Here are some things you could try, in addition to the more typical courses, language classes, apps, and textbooks:

- Making flashcards

- Keeping a journal

- Following Icelandic vloggers or social media influencers

- Watching movies and documentaries in Icelandic

- Joining Icelandic-language forums and Facebook groups

- Listening to podcasts, radio shows, and Icelandic music

Be realistic, though. If you only have 30 minutes spare a day, you can’t watch a movie, read a novel, write an essay, and study your flashcards every week.

Rather than pushing yourself too hard, be kind to yourself and create a schedule that gives you time to do it all – and still feel relaxed. This will keep you motivated. In fact, you’ll probably end up making more progress over the course of a year than you would with a dispiritingly intense study schedule.

That being said, try to study five or more days a week, even if it’s just for 10 minutes at a time. It’s better to practice regularly than to cram it all in on Sunday. This is especially true if your goal is to think in Icelandic or achieve fluency.

If you skip a day (or two, or five), don’t beat yourself up about it, though. Everyone gets off track sometimes, and besides, you can’t change what you did yesterday. Just accept that it’s happened and start again.

Similarly, if you feel like you’re not making enough progress, have patience. It takes a long time to learn a language, and sometimes a task that seemed easy yesterday can feel impossible today. However, as long as you’re consistently studying, you will improve.

To see just how far you’ve come, try going back to something you watched, read, or wrote a few months ago. Never compare yourself to yesterday: too many factors, such as tiredness and the amount of time you’ve spent using your native language, can affect your Icelandic.

Finally, focus on the things you’ve done in Icelandic that you enjoyed or are proud of – whether that’s debating politics over drinks in Reykjavik or successfully asking someone to take a photo of you in front of Jökulsárlón.

What’s the Best Way to Learn Icelandic?

The best way for you to learn Icelandic depends on your own learning style. You may find that you learn more quickly in a traditional classroom setting (and if your local community college does not offer classes in Icelandic, you can always try a tutor online instead).

Or you may do better in self-directed study, using an app for the framework of your course and adding on enrichment activities like Icelandic TV shows.

If you learn easily from reading, a textbook will give you a great leg up on Icelandic grammar. But if you have more of an auditory learning style, seek out an app or YouTube video where someone else explains the grammar concept out loud.

Is Icelandic Hard to Learn?

If you were to ask the US Foreign Services Institute, they would tell you that Icelandic is a “hard language.” Their data shows that it requires an average of 1,100 classroom hours for an English speaker to reach “Professional Working Proficiency” in the language, making it more difficult than German or Spanish, easier than Arabic or Chinese, and roughly as challenging as Hungarian, Armenian, and Vietnamese.

Many language learners agree that it’s difficult. They’ll often point to the grammar, which is slightly more complex than other Scandinavian languages, and the linguistic purism that means you can’t get away with saying “computer” in an Icelandic accent – unless you want the listener to switch to English, that is.

Yet don’t write Icelandic off just yet: it’s worth the hard work. Plus, there are several factors in its favor.

Breaking Down the Icelandic Language: A Guide for English Speakers

The Alphabet

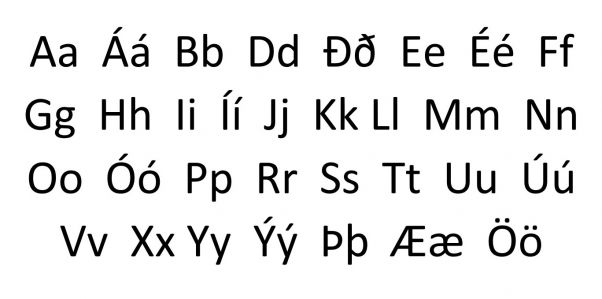

There are 32 letters in the Icelandic language, and most of them are also used in English.

The exceptions are Ðð, Þþ, and Æ, as well as the accented vowels (Á, É, Í, Ó, Ú, Ý, and Ö). Unlike in Spanish or French, these are considered separate characters: the accent changes how the vowel is pronounced.

C, Q, W, and Z are rarely used, and many people don’t consider them to be part of the alphabet. The first three only ever appear in loanwords (which aren’t very common in Icelandic), while using Z is considered outdated.

Pronunciation

While Icelandic has a few new sounds for you to master, the pronunciation is fairly standard. Most words are phonetic, and all letters are voiced. Stress is regular: it’s either on the first syllable or, in certain prefixed words, on both the prefix and the first syllable of the root word.

Plus, thanks to Iceland’s small size, you won’t have to battle your way through understanding different accents or dialects.

You can practice your pronunciation with this YouTube video, or if you’re from the US, you might find this video helpful. Alternatively, read through this guide.

Vocabulary

Icelandic purism means loanwords are rare, although not unheard of: “coffee,” for example, translates to kaffi. Yet by and large, the Icelandic Language Institute successfully creates Icelandic words for modern technology and trends.

Some people complain that this means you have to learn even more words, yet there are benefits to this system.

These new Icelandic words, such as tölva (computer), rafmagn (electricity), and myndband (video), are normally logical compounds of other words. When you learn them, you’re also picking up additional and conceptually connected Icelandic vocabulary.

Tölva, for example, comes from tala (number) and völva (prophetess), making your computer a prophetess of numbers. Rafmagn combines raf (amber) and magn (power): electricity is amber power. Myndband is made up of mynd (picture) and band (tape, string): video is, quite literally, images on a tape.

You’ll also discover that most Icelandic places’ names are made up of a list of relevant nouns. Vatnajökull, for example, combines vatna (water) and jökull (glacier), while Reykjavik translates to “bay [vik] of smokes [reykja].”

For analytical learners who find it easier to memorize words through patterns, this can make Icelandic word lists slightly less challenging. And if you’re planning a road trip around this small but scenic country, you’ll come back not just with amazing memories but also an expanded vocabulary.

Syntax, aka Word Order

Generally, just like in English, Icelandic has a subject–verb–object sentence structure. And just like in English, the verb moves to the front for yes-no questions. (“You are hungry. Are you hungry?”) However, there are some exceptions to this structure, especially in embedded clauses and poetry.

Let’s put poetry to one side, and instead look at what main and embedded clauses are. “The child reads the book” is both a full sentence and a main clause. “The child, who out of all the children is the only one not wearing a green t-shirt, reads the book” contains an embedded clause (“who out of all the children is the only one not wearing a green t-shirt”) inserted into the main clause.

In Icelandic, the verb is always the second grammatical component of an embedded clause – even if that means the subject comes later. This is called V2 word order. We sometimes see this structure in English, although not normally in embedded clauses. For example, you might say: “Here comes the mayor” or “Never will I ever do that”.

As for negation, this is pretty easy: adding ekki after the verb will make any sentence negative.

Inflection

Inflection is the reason why Icelandic has a reputation for being “hard.” It means that words change their form in order to convey extra meaning, while remaining within their grammatical category (verb, noun, adjective, adverb…). That might sound vague or confusing, so here are some examples in English:

- “Be,” “am,” “are,” and “is” are all inflections of the same verb. They never stop being verb (their grammatical category), but the word changes to give extra information about who or what the subject is.

- “Disappear” and “disagree” are inflected versions of “appear” and “agree:” the words remain verbs, but prefixing them with “dis-” means that they carry their opposite meaning.

- The change from “happiness” to “happy” isn’t an example of inflection because the word goes from being a noun to an adjective. The grammatical category changes.

- The change from “happy” to “happier” is an inflection, however: both words are adjectives, but one is comparative.

There are many types of inflections. When verbs change to reflect the time (eat/ate/have eaten) or subject (eat/eat/eats), it’s called conjugation. When nouns, adjectives, pronouns, and words with other grammatical functions change, it’s often called declension.

Icelandic inflects a lot, which means you’ll spend more time memorizing grammar tables and identifying the grammatical functions of words. If you already speak German or Dutch, you’ll likely find this helpful, since the languages have quite a bit in common.

The positive side is that the inflection is probably the most frustrating part of learning Icelandic: the rest of the language is fairly accessible for English speakers.

Let’s explore some of the ways that Icelandic does – and doesn’t – inflect.

Nouns

Nouns inflect for several reasons.

Gender

Icelandic has three genders – male, female, and neuter. In other words, when you want to write that a woman is reading an Icelandic saga, both the woman (kona) and the saga (saga) are feminine.

Case

This means the word form reflects its role in the sentence. Think about the way we say “I” or “me” in English: we use “I” when we’re the object and “me” when we’re the subject. In Icelandic, we see cases used for nouns as well, and there are four of them: accusative, nominative, dative, and genitive.

For example, if a man sees a horse, he is the subject (nominative) and the horse is the direct object (accusative). You would say: “The man [nominative] sees a horse [accusative].”

If he gives a horse to a friend, a second, indirect object appears: the friend (dative). It becomes: “The man [nominative] gives a horse [accusative] to his friend [dative].”

And if he tells his friend the horse’s name, he’ll then use the genitive case for “horse” to show it’s the owner of the name. It’s the equivalent of saying “the horse’s name” or “the name of the horse” in English.

A sentence with all four cases can get pretty confusing, but just think about who’s doing what in the sentence. For example, you would say: “The man [nominative, because he’s the “do-er”] tells his friend [dative, because the friend is the recipient] the horse’s [genitive, because the horse is the owner of what comes next] name [accusative, because it’s the object being given].”

Number

Just like in English, Icelandic nouns can be singular or plural.

Article

In English, you might say “an apple” (using the indefinite article) or “the apple” (using the definite article). In Icelandic, you don’t need to do anything if it’s “an apple:” the indefinite article doesn’t exist, meaning “apple” (epli) and “an apple” (epli) are identical. However, the definite article does exist. In everyday speech and writing, you’ll add it as a suffix to the noun (eplið).

While this might sound complicated, don’t worry: once you’ve done a few exercises and drills, it should start to make more sense.

There are some positives, too. For example, certain prepositions always go with certain cases. If you would use “to” when saying something in English, you’ll know that you need the dative case when speaking in Icelandic.

Plus, there are far fewer cases than in some other languages, for example, Russian or Polish. And once you’ve understood the case system, you’ll be in a good position to pick up other Germanic languages.

Verbs

There are several verb groups that will determine how a verb is conjugated. If you’ve ever studied a Romance language, such as French or Spanish, this will be familiar to you.

Just like in English, you’ll also need to conjugate verbs based on their tense, person, and mood. This will seem a lot more similar to English speakers than noun cases.

For example, Icelandic verbs have four moods – which is only one more than English. These are the indicative (“He does it”), imperative (“Do it!”), conditional (“she would do it”), and subjunctive (“If she were to do it…).

There is one thing that might surprise you, though: the mediopassive or middle voice. In English, we choose between the active and passive voice to reflect whether the subject did something or had something done to it. In Icelandic, there’s a third option.

- “The girl closed the car door” → you would use the active voice in both English and Icelandic

- “The car door was closed (by the girl)” → you would use the passive voice in both English and Icelandic

- “The car door closed” → although you would use the active voice in English, you would use the mediopassive voice in Icelandic

Even if “the car door” is the subject of the sentence, it cannot close itself. It needs some form of external force to do so. And that’s why, in Icelandic, you use the mediopassive voice to say bílhurðin lokaðist.

You can also use the mediopassive voice in reported speech, reflexive actions, and some other situations. You’ll normally recognize it by a “~st” ending, like above with “lokaðist.”

Be careful with automatically adding it, though – sometimes this small suffix can dramatically change a word’s meaning, especially when you get into the realm of reflexive verbs. But that’s something best learned on a word-by-word basis.

Adjectives

Adjectives must agree with the gender, number, and case of the noun they’re modifying. While this means you will have some more inflection tables to memorize, most of them are fairly regular. Just be careful with góð, or “good,” which not only breaks the rules but is also a word you’ll probably use quite a lot.

Adverbs

Good news! Adverbs don’t inflect beyond comparisons, i.e. the equivalent of soon–sooner–soonest in English. Plus, many adverbs can be created by adding ~lega to an adjective, much like how we use “~ly” in English.

Pronouns

In some ways, this will seem pretty similar to English. You have your personal pronouns (I, they), reflexive ones (myself, themselves), possessive (mine, theirs), demonstrative (this, that), and indefinite (some, anybody). You will, however, need to decline them based on the relevant case and whether they are singular or plural.

By now, you’ve probably realized that studying Icelandic grammar requires a firm understanding of sentence structure and patience when memorizing inflection tables. If that feels like a challenge, we get it. But stay patient: it’s worth all the work. When you finally feel confident with the mediopassive voice or realize that you don’t need to think about which case to use, you’ll feel proud of how far you’ve come.

Besides, Icelandic has a lot of things going for it: the accessible pronunciation and alphabet, the fascinating literature, the stunning landscapes and travel opportunities, the exciting history… and you’ll be doing a lot more than just studying the grammar, after all.

What’s the Easiest Way to Learn Icelandic?

The easiest way to get into a language like Icelandic is with some guidance, either through a structured app-based course, an in-person course, or a course presented by a tutor. This can help a lot especially if you have never learned another language before. Having a structure helps you logically move through the language, without skipping over key areas.

If you are an experienced language learner, you may find it easier to cobble together your own learning resources using some of the tools mentioned in this article.

How Long Does it Take to Learn Icelandic?

The Foreign Services Institute, or FSI, estimates that it takes most English speakers around 1,100 hours of dedicated study or class time to gain a working proficiency in Icelandic. If you can commit to one hour of serious study a day, learning Icelandic will likely take you about three years.

But this also depends on why you want to learn Icelandic. If you want to know enough to travel without getting lost, you may need just a few months of study. If you plan to move to Iceland, you will probably learn much more quickly because of the total immersion.

How to Learn Icelandic Fast

While there are many great tools that can help you learn Icelandic in the way that works best with your learning style, there is no perfect hack to learn Icelandic fast. As with any language, the best way to learn more quickly is to block out regular study time every day and stick to it.

You may also learn more quickly through creating a semi-immersive environment by surrounding yourself with the sounds of Icelandic as often as possible. For example, you could download an audiobook in Icelandic to listen to on your way to work or school. Even if you can’t understand every word just yet, listening to the flow of the language can help your brain start to recognize its sound.

How to Speak Icelandic

The best way to learn to speak Icelandic is to listen to native speakers as much as possible. If you don’t have the privilege of visiting Iceland or know any native speakers, you can always use online resources.

Besides immersing yourself in the sounds of the language, make sure you also practice speaking! You may not get the pronunciation perfect on your first try, but the only way to get better is to practice. Finding a conversation partner online is a great way to develop your pronunciation in a safe space.

Where to Learn Icelandic: Additional Icelandic Learning Aids

There are lots of other tools that can be of great help when learning Icelandic. With these resources, you can elevate your Icelandic learning experience and expose yourself to the language in different contexts.

Icelandic Textbooks and Reference Books

The beginner-level Íslenska fyrir alla is available for free. Since it’s completely in Icelandic, you might find it easier to work through with a tutor.

Colloquial Icelandic is a fairly comprehensive English-language Icelandic textbook. You can listen to the supplementary audio recordings here for free.

Hippocrene Beginner’s Icelandic is another popular English-language option. Some people consider it slightly more accessible for beginners than Colloquial Icelandic.

Complete Icelandic: Beginner to Intermediate is published by a well-known brand, but some students find its grammatical explanations are too brief. If you want to use the audio content, make sure to buy a hard copy rather than the ebook.

Íslenska fyrir útlendinga is praised for its thorough breakdown of Icelandic grammar. Bear in mind that it doesn’t use English at all, so you’ll need to already have a foundation in Icelandic. You can also buy the accompanying workbook.

If shopping on Amazon, you might come across Icelandic: Grammar, Text, Glossary. Having been published in the 1940s, the language can be extremely dated and there’s an intense focus on grammar. The print can also be hard to read. However, some Icelandic learners like to use it as a supplementary tool alongside other textbooks.

Icelandic Fiction: Books, Sagas, and Poetry

Book lovers are spoiled in Iceland. People write, publish, and read more books here than they do anywhere else in the world. It’s also the most popular Christmas present in the country. After all, January nights are long when you’re this far north.

In fact, confess that you don’t like reading, and depending on how polite the Icelander is, you might hear blindur er bóklaus maður – blind is the man without any books.

Fortunately, you’ve got some riveting Icelandic fiction to choose from. Start off with texts designed for language learners, like Sagnasyrpa, a collection of short stories in Icelandic that slowly became more difficult. The University of Wisconsin also has bilingual texts online.

If you’re interested in Iceland’s Viking and Nordic history, you’ll probably want to read at least one of the sagas. Njál’s Saga is one of the most popular ones and spins a tale of divorce, crime, and trials at Alþingi. The Eddas, meanwhile, deal with the far less prosaic world of Nordic mythology.

Halldór Laxness is a Nobel Prize-winning twentieth-century writer. Try Gerpla, his take on a modern Icelandic saga, or Salka Valka, the powerful story of an unconventional woman in rural Iceland.

Gerður Kristný also draws on Iceland’s literary traditions. In her award-winning poem Blóðhófnir, she retells a Nordic myth from a female perspective – something that can make for dark and emotional reading.

If you like spooky stories that evoke the Icelandic countryside, give Yrsa Sigurðardottir’s short stories a go. Or, if crime fiction is more your style, read Mýrin by Arnaldur Indriðason.

Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir’s award-winning Ör is the story of a man who feels stuck in an unhappy life and has to decide whether or not to start over.

Sjón’s Skugga-Baldur is hard to forget: a surreal, historical novel that touches on modernity, slavery, mental health, family ties, and the treatment of people with Down’s syndrome.

Conventional chick-lit is generally hard to find in Iceland, but there are lots of plenty of books focused on the female experience. Klisjukenndir by Birna Anna Björnsdóttir explores a young woman’s relationships with her partner and herself.

Unable to find Icelandic-language books where you live? Read Icelandic poetry on the Tumblr account Íslensk ljóðlist.

Alternatively, if you’re more of an audiobook fan, try Hljóðbók and Hljóðbókasafn Íslands.

News, Music, and Other Resources for Learning Icelandic

Listening to songs can help embed vocabulary and get you to spend more time thinking in Icelandic. Fortunately, Iceland’s thriving music scene means it’s not hard to find bands to listen to – especially if you’re a fan of indie, folk, and rock.

Bear in mind that some Icelandic bands, such as Of Monsters and Men, prefer to sing in English. Meanwhile, Sigur Rós not only switches between Icelandic and English but also sings in Hopelandic, or as they describe it, “a form of gibberish vocals… that acts as another instrument.” Do your research (or listen on YouTube or Spotify) before buying an album.

In addition to Sigur Rós, artists who sing at least some songs in Icelandic include Björk, Árstíðir, Kaleo, Hatari, Egó, Ásgeir Trausti, Kid Isak, Émmsje Gauti, Sólstafir, and Jónsi. You can also listen to playlists like this one to discover artists you might like.

Try reading the news in Icelandic, too. Not only will it introduce you to new vocabulary and push you to recognize nuance, but it’ll keep you up to date on the issues important to everyday Icelanders. Say halló to suddenly having something to talk about beyond the weather, or understanding the memes and hashtags that appear on social media.

Since every newspaper has its own editorial bent, it’s worth reading a few to find ones that appeal to you. Morgunblaðið is widely read, and you might also like Fréttablaðið, Visir, and RÚV.

Wondering what Icelanders thought of the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull, WWI, or even the bubonic plague? Check the archives at Tímarit: their collection of newspapers and magazines dates back centuries, with over 60,000 articles in total.

With all this reading and looking up lyrics, you’ll need a dictionary. Unfortunately, there are limited free yet good English-Icelandic options. This one is from the University of Wisconsin and can help you out if you’re just starting with Icelandic. When you’re ready to read definitions in Icelandic, give Málið a go.

Glosbe is another option. It’s made up of contributions from users, so some definitions may be inaccurate. On the other hand, it’s more likely to include modern slang than some others. Or, if you’re willing to pay for a bilingual dictionary, try Snara.

And, if you’re not sure how to pronounce something, check out how other people are saying it on Forvo.

Although learning Icelandic might seem challenging, you’ll soon discover that there are many opportunities to practice it. And whether it’s reading the Sagas, ordering plokkfiskur while traveling, or chatting about music with friends in Reykjavik, there’s nothing like the feeling of successfully doing it in Icelandic. So, what are you waiting for?